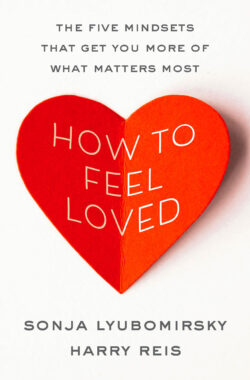

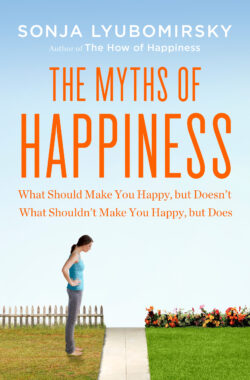

Sonja Lyubomirsky, Ph.D., is a Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Riverside, and author of The How of Happiness and The Myths of Happiness (published in 39 countries). Her most recent book, How To Feel Loved (with Harry Reis), was released in February, 2026. She received her B.A. summa cum laude from Harvard University and her Ph.D. in social psychology from Stanford University. Lyubomirsky’s research—on the possibility of lastingly increasing happiness via gratitude, kindness, and connection interventions—has been the recipient of many grants and honors, including an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Basel, the Diener Award for Outstanding Midcareer Contributions in Personality Psychology, the Christopher J. Peterson Gold Medal, AAAS Fellow, the Faculty Research Lecturer Award (campus-wide), and a Positive Psychology Prize (H-index = 96). She lives in Santa Monica, California (USA), with her family. Watch her recent TED talk here.

About Sonja Lyubomirsky

SONJA LYUBOMIRSKY

=== pronounce my name ===

Distinguished Professor, University of California, Riverside

Ph.D. Stanford University, 1994

DISCOVER HOW TO CULTIVATE EVER MORE HAPPINESS AND EASE

I’ve partnered with my friend Lauren Weinstein, an executive coach who’s worked with Fortune 500 leaders, to share simple, science-backed tools that help you feel better and do better.

To this end, we created the Elevate Membership — not another program to complete, but a weekly space for insights that bring more calm, clarity, and flow into your days.

In just 30 minutes a week, you’ll learn science-backed tools to feel better, stress less, and achieve more.

Research Areas

Why Are Some Happier?

I have always been struck by the capacity of some individuals to be remarkably happy, even in the face of stress, trauma, or adversity. Thus, my earlier research efforts had focused on trying to understand why some people are happier than others (for a review and theoretical framework, see Lyubomirsky, 2001).

Benefits of Happiness

Is happiness a good thing? Or, does it just simply feel good? A review of all the available literature has revealed that happiness does indeed have numerous positive byproducts, which appear to benefit not only individuals, but families, communities, and the society at large (Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005; see also Walsh, Boehm, & Lyubomirsky, 2018; Walsh, Boz, & Lyubomirsky, 2023).

Happiness Interventions

A vibrant and continuing program of research is asking the question, “How can happiness be reliably increased?” (for reviews, see Layous & Lyubomirsky, 2024 (forthcoming in Handbook of Social Psychology); Layous & Lyubomirsky, 2014; Lyubomirsky, 2008; Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013; Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, & Schkade, 2005; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009).

Hedonic Adaptation

Finally, a line of research focuses on hedonic adaptation to positive experience as a critical barrier to raising happiness (Bao & Lyubomirsky, 2013; Lyubomirsky, 2010; Sheldon et al., 2012; Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012). After all, if people become accustomed to (and take for granted) anything positive that happens to them, then how can they ever become happier?

The Science of Happiness

The Science of Social Connection

Ph.D. Students

Recent Media Appearances

-

FILM

-

Mission Joy: Finding Happiness in Troubled Times; available on Netflix, Amazon Video, etc.

-

-

PODCAST

-

TV INTERVIEW

-

The Whole Story with Anderson Cooper: Miracle on the Hudson; available on CNN & Max.

-

- PRINT

- New York Times Magazine — “How Nearly a Century of Happiness Research Led to One Big Finding”

- Fortune — “5 Simple Strategies Can Help You Be Happier At Work”

- Los Angeles Times — “Be Grateful For What You Have. It May Help You Live Longer”

- UCR Inside — “Sonja Lyubomirsky Wins Top Faculty Award for 2023-24”

- Highlights Magazine — “Why Be Kind”

- UCR Magazine — “Tuning in Again to Psychedelics”

Subjective Happiness Scale

- Permission is granted for all non-commercial use, including scholarly/academic.

- A PDF of the scale can be downloaded here.

- The scale is available from the first author in the following translations: Bulgarian, Chinese, Croatian, Danish, Dutch, Estonian, Filipino, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Gujarati, Hebrew, Hungarian, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Malay, Norwegian, Persian, Peruvian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Scandinavian, Serbian, Sinhala, Slovak, Spanish (European), Spanish (Mexican), Swedish, Tamil, Thai, Turkish, Urdu. If you created a new translation, please contact us! (sonja.lyubomirsky[at]ucr.edu)

- To score the scale, reverse code the 4th item (i.e., turn a 7 into a 1, a 6 into a 2, a 5 into a 3, a 3 into a 5, a 2 into a 6, and a 1 into a 7), and compute the mean of the 4 items. Norms are available in the reference below, as well as in many other publications that have used the scale (see PsycInfo). Note: You may omit the 4th item and only use the first three items.

- Please cite the following scale validation paper in all work mentioning the scale.

- Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46, 137-155. The original publication is available at www.springerlink.com.

Publications

My three books are below. All the publications and scholarly papers can be downloaded for free (links provided).